“100% preventable, with no cure,” Upstate researchers’ paper defining accelerated silicosis could help diagnose disease that continues to impact workers around the world

Almost four decades in the making, Upstate researchers have published a paper that made the cover of the March 2024 issue of the American Journal of Industrial Medicine. Analyzing research and data from sandblasters in Texas exposed to silica in the 1980s, they were able to clearly define a level of silicosis (called accelerated silicosis) that can evade detection through usual diagnostic measures. Silicosis outbreaks have been making news recently, as concerns are raised over the impact on engineered stone countertop workers. Citing the potential health dangers, the state of California has imposed emergency regulations on the industry. Some countries, such as Australia, have banned engineered stone products entirely. Researchers hope that by clearly illustrating what accelerated silicosis looks like, they can help medical professionals come to earlier and more accurate diagnoses; creating better outcomes for patients and raising awareness about the dangers of silica exposure.

From left to right; Soma Sanyal, MD, Assistant Professor of Pathology, Jerrold Abraham, MD, Director of Environmental/Occupational Pathology, & Judith Crawford, PhD, Pathology researcher.

Jerrold Abraham, MD, is the director of Upstate’s Environmental/Occupational Pathology Division, and a professor of pathology. It was almost forty years ago when he first started working with a former medical school classmate (University of California at San Francisco [UCSF], Class of 1970) who was seeing cases of silicosis that were hard to diagnose in workers who were performing sandblasting on oil field pipes.

“[The workers] were sick, but the chest X-ray didn't show what they were expecting to find,” explains Abraham. “They were turned down for workers’ compensation because of the regulations in place that required positive findings on a regular chest x-ray.”

His former UCSF classmate and pulmonologist Stephen Wiesenfeld, MD, was the one to identify the unusual group of patients in Texas.

“They were coming down with symptomatology of silicosis much earlier than most patients,” says Wiesenfeld. “Usually, chronic silicosis shows up with some symptoms after 20–30 years of exposure and an abnormal chest x-ray. We were seeing patients who, after less than a 10-year exposure, were acutely ill but with normal screening chest x-rays. We were able to follow most of them prospectively and found that a high-resolution CT pulmonary scan was more sensitive in detecting early micronodular densities. As x-rays progressed to more massive fibrosis and scarring, this progression correlated with increasing silica concentrations in the lungs.”

Stephen Wiesenfeld, MD, Pulmonologist who recognized the group of patients had cases of silicosis not detectable by typical diagnostic tests.

Abraham and Wiesenfeld realized this was a chance to define “accelerated silicosis” clearly for the first time. The accelerated designation falls between the chronic and acute progressions of silicosis. There are documented cases of acute silicosis that can develop after a year or less of intense exposure to silica particles. This middle ground of accelerated silicosis had yet to be fully described.

“It doesn't show up on the X-ray yet because it hasn't had time to form those little round scars that show up nicely on an X-ray or form classic silicotic nodules that will be found during a biopsy,” says Abraham. “One of the main contributions from this article is the two-page spread on the pathology showing the readers, ‘what does this disease look like?’ You don't see that anywhere in the literature currently. For pathologists who are trying to wrestle with a diagnosis, that’s available to them now. We hope this will help physicians have the proper knowledge to diagnose silicosis in their patients.”

Judith Crawford, PhD, is a researcher in Upstate’s Pathology department and was brought on board the project recently to help analyze the data originally gathered from Wiesenfeld’s patients. She highlights the importance of the paper clearly laying out the pathology of accelerated silicosis as well as findings about worker exposure to silica. “We found that sandblasters who worked with recycled sand until it became too fine for use had a greater intensity of exposure to silica. These people had higher silica concentration in the lung, more severe disease, greater mortality over a shorter time period and at younger ages than those without the intense exposure.”

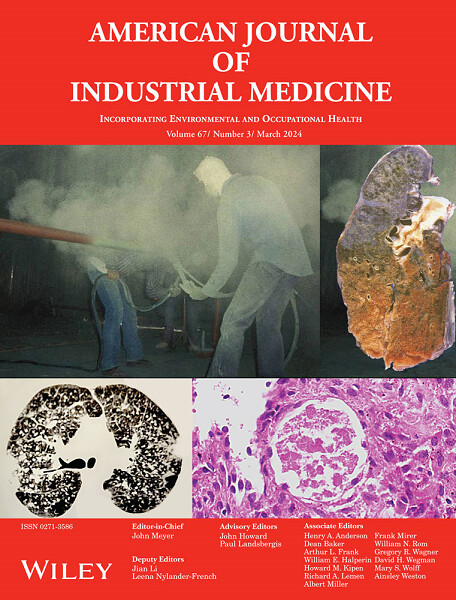

Cover of the March 2024 issue of the American Journal of Industrial Medicine featuring images from the article "Accelerated silicosis in sandblasters: Pathology, mineralogy, and clinical correlates".

“Jerry and I are excited that we got this thing published and it's out there for other people to see and hopefully it'll be of use,” says Wiesenfeld. He and Abraham hope studies like theirs can raise awareness about the causes and dangers of silica exposure; a concern that reaches far beyond the sandblasters in oil fields they initially studied. Silicosis is seen from the denim industry sandblasting material to create distressed denim, to coal miners, and to the current concerns over the countertop manufacturing industry across the globe. “This keeps showing up all over the world,” says Abraham.

Just this past year, Australia banned engineered stone (quartz) countertop material, because of the danger the manufacturing and cutting of the material poses to workers. Ikea is in the process of phasing out engineered stone, and California has put emergency regulations in place as officials work to find long-term solutions to protect workers.

“Engineered stone can be as much as 90% silica, so it’s extremely dangerous when silica dust is created by machining such as cutting, grinding, sanding, drilling or polishing. Strict controls are critical to protect workers from exposure,” explains Crawford.

“We showed that this disease that happened back then is still relevant to what's going on now,” says Abraham. “Using a very sophisticated analysis of all the dust exposures, we showed that the silica was the main driver of all the observed abnormalities.”

Crawford emphasizes why awareness and prevention are so important. “Silicosis is a lung disease that has no cure. The only thing that can be done to help people is a lung transplant. It's a dire situation, and prevention is everything.”

“We are encouraged by this publication,” adds Wiesenfeld. “Hopefully it'll be of use. I think the level of awareness has to go up a few notches around the country for fewer people to develop this condition.”

You can read their full study online here- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ajim.23561

Bryan Burnett, MS, forensic scientist

The other important contributors to this paper are Dr. Soma Sanyal, an Assistant Professor of Pathology at Upstate, and Bryan Burnett, a forensic scientist in California.

You can also learn more about the impact on quartz stone manufacturing workers and the industry in California here- https://www.cbsnews.com/news/workers-who-cut-quartz-countertops-say-they-are-falling-ill-from-a-deadly-lung-disease/